The service was held on Thursday, 27 November 2025 at 11:30 AM at the Centennial Park Cemetery in Adelaide, Australia.

Childhood and Youth in Iran (1943–1970)

Born on 7 December 1943 in Babol, Mazandaran, in northern Iran, Vajiheh Ighani (later Vaezi) was raised in a committed Bahá’í home. Her mother, Maliheh Sabetian, was a schoolteacher from a large family that included two sisters and several brothers. When Vajiheh was very young, her parents separated. Maliheh lived in another town due to her teaching job, entrusting her daughter to the care of her grandparents—whom Vajiheh loved dearly.

Vajiheh was raised essentially as an only child, surrounded by love in her grandparents’ home. She thrived under their gentle encouragement and was given one clear instruction: “Just focus on your studies.” Unusual for the time, they discouraged her from doing chores or cooking, preferring her to excel academically and teach the Cause.

Although her father, Zikrullah, eventually remarried and had several more children, Vajiheh was not involved in his new family. A single photograph taken in 1973, showing her with her father and one of her step-sisters, remains the only record of that connection.

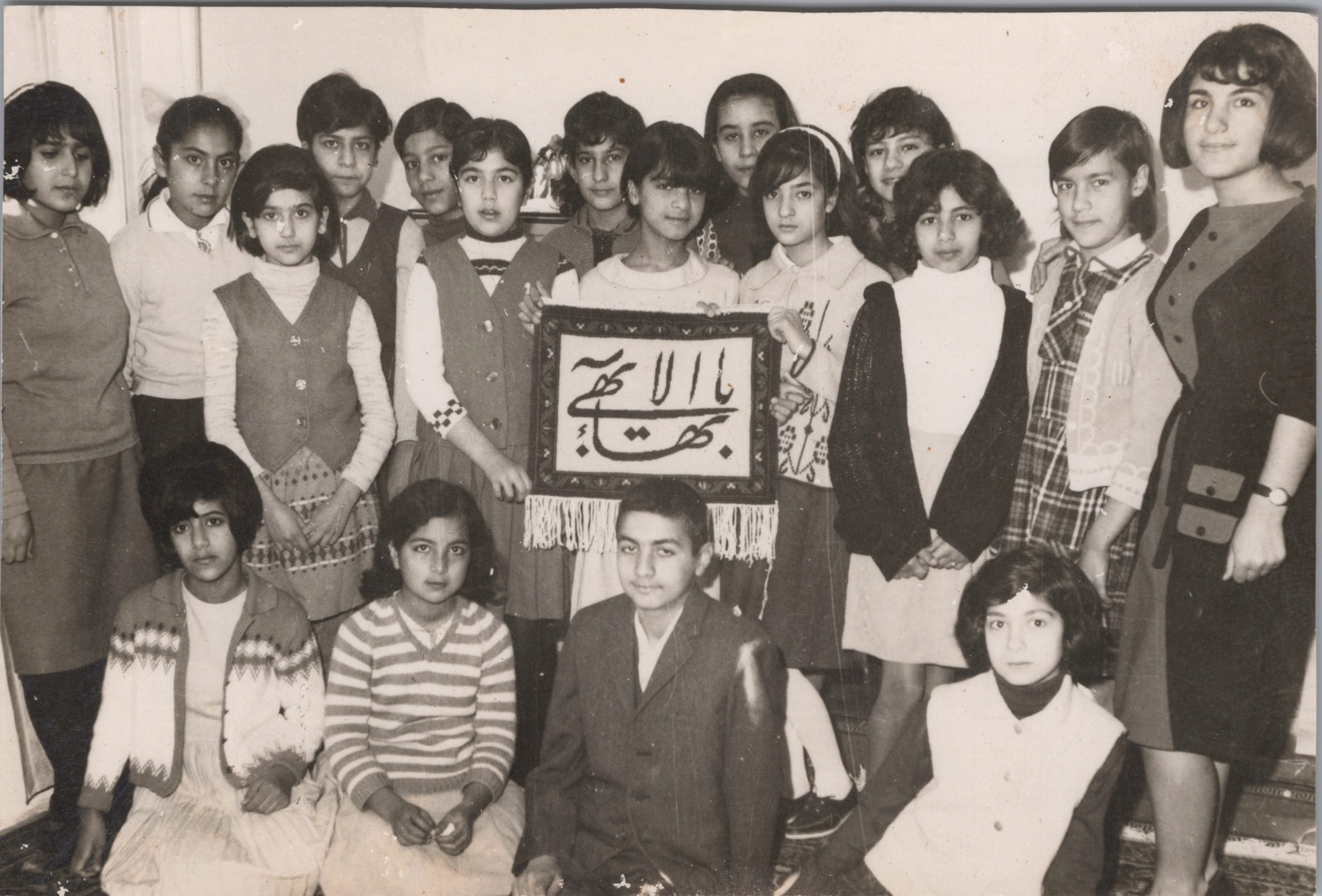

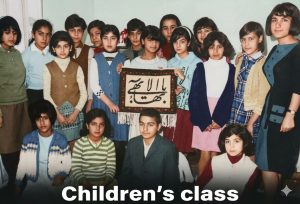

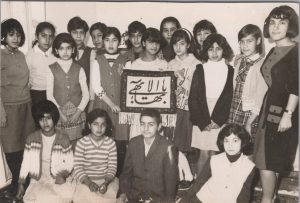

From her earliest years, Vajiheh was immersed in the Bahá’í Faith. Her maternal uncles were ardent travel teachers who regularly visited villages in Mazandaran to share the teachings of Bahá’u’lláh. Even as a young girl, Vajiheh accompanied them on these trips. She attended Bahá’í moral education classes, which in those days went all the way up to year 12, after which she taught these classes herself.

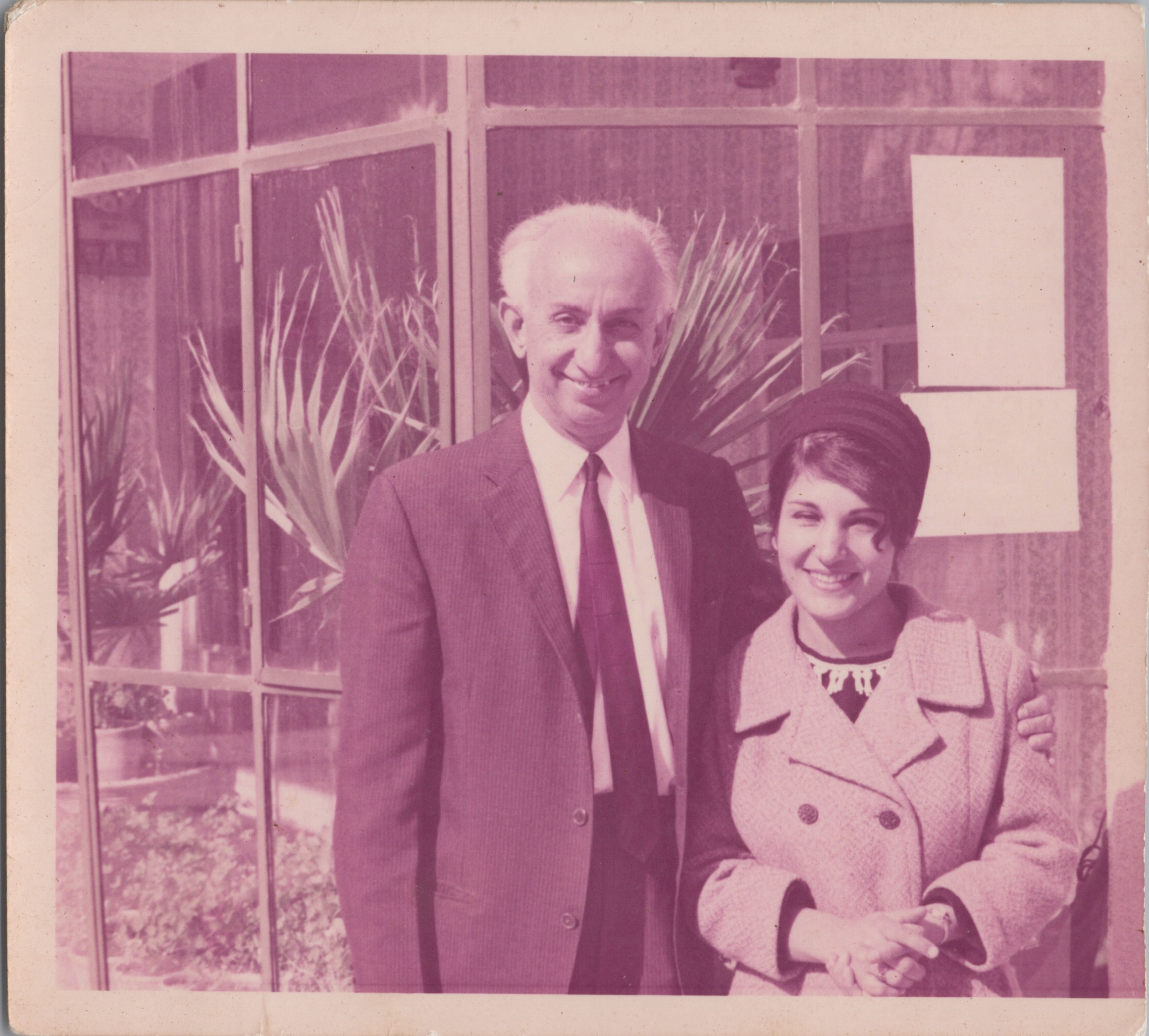

In her late teens, she moved to Tehran to attend university. At the University of Tehran she enrolled in the Faculty of Pharmacy. She also joined an intensive four-year Bahá’í studies course taught by the renowned teacher Dr. Ghadímí. Dr Ghadímí’s classes were transformative; they were designed to deepen the youth and inspire them to arise for teaching and pioneering – leaving their homes to establish communities in foreign lands. Photographs remain of Dr. Ghadímí and of the entire class.

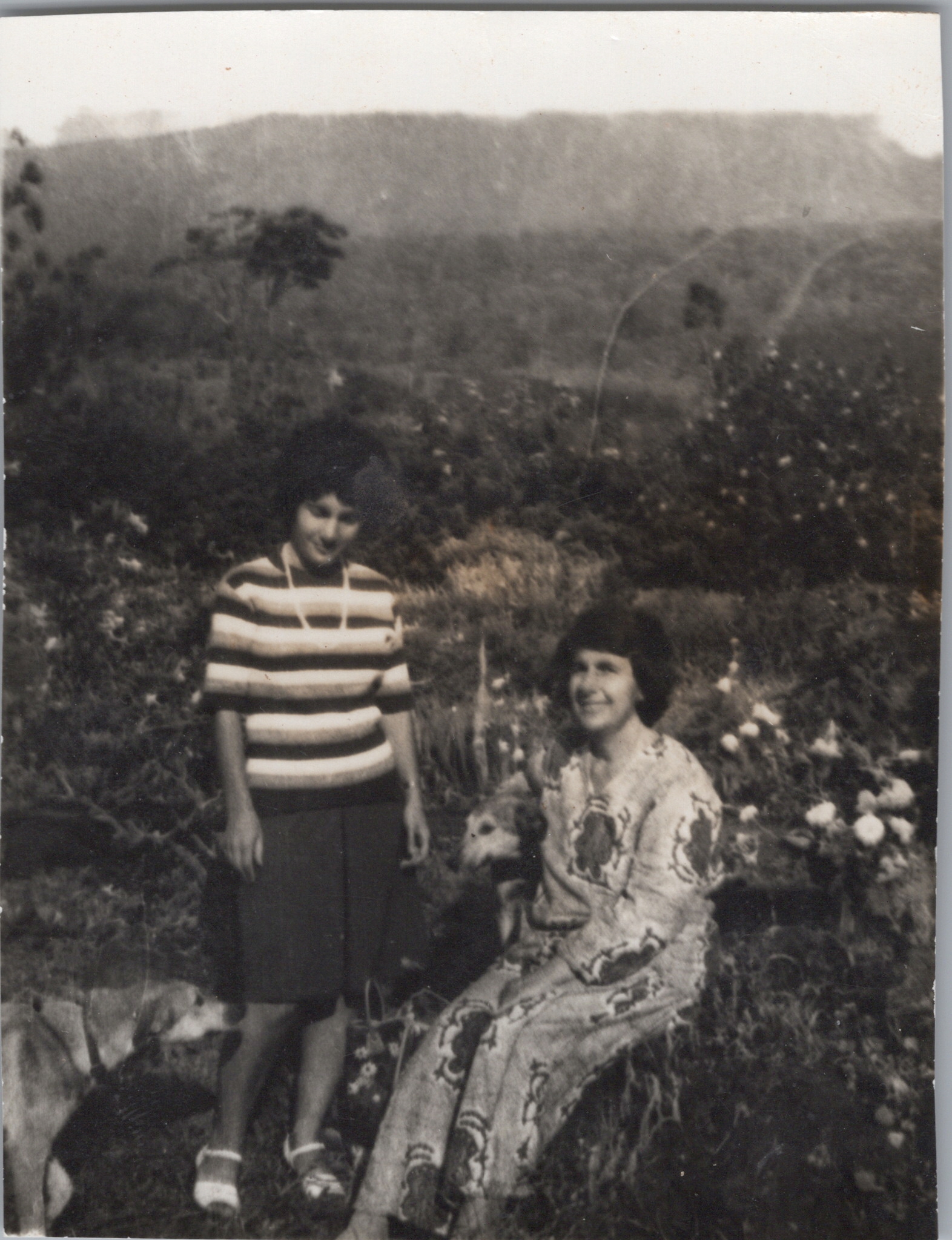

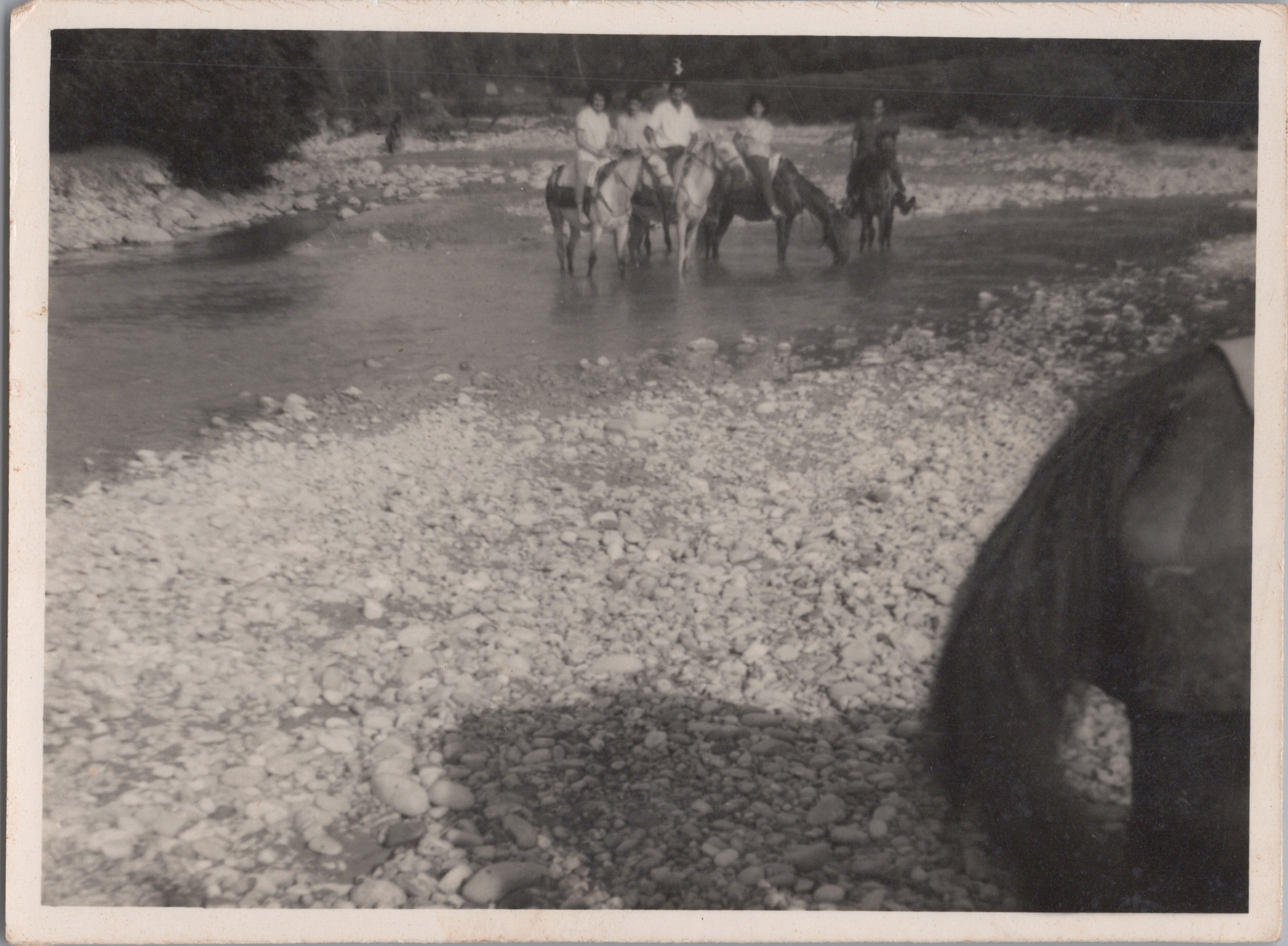

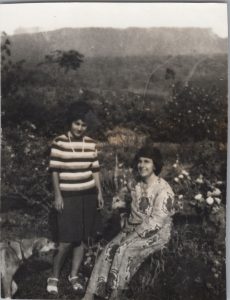

She met Behin Paravarpisheh (Newport) who was a classmate in both Dr Ghadímí’s class and the University. These two formed a lifelong friendship, we have several photographs of them in social settings and at Baha’i gatherings, and they continued their correspondence throughout Vajiheh’s life. On one occasion, they went for an outing and rode a horse – an example of how they encouraged each other in their adventures.

It was also during this period that Vajiheh first felt the irresistible call to pioneer. The beloved Guardian, Shoghi Effendi, had repeatedly urged the Bahá’ís of Iran — the spiritual descendants of the Dawn-Breakers — to scatter across the globe and carry the healing message of Bahá’u’lláh to every land.

Vajiheh initially hoped to study abroad so she could teach the Faith while completing her degree, but her family felt she was too young to leave the country alone. She therefore finished her pharmacy degree in Tehran, worked for six months, and then began to look for an international pioneering post. Even this plan met with disapproval from most relatives, who felt a young, single woman should not travel alone, particularly overseas. Yet, Vajiheh’s mother was the sole exception, offering specific support for her pioneering aspirations.

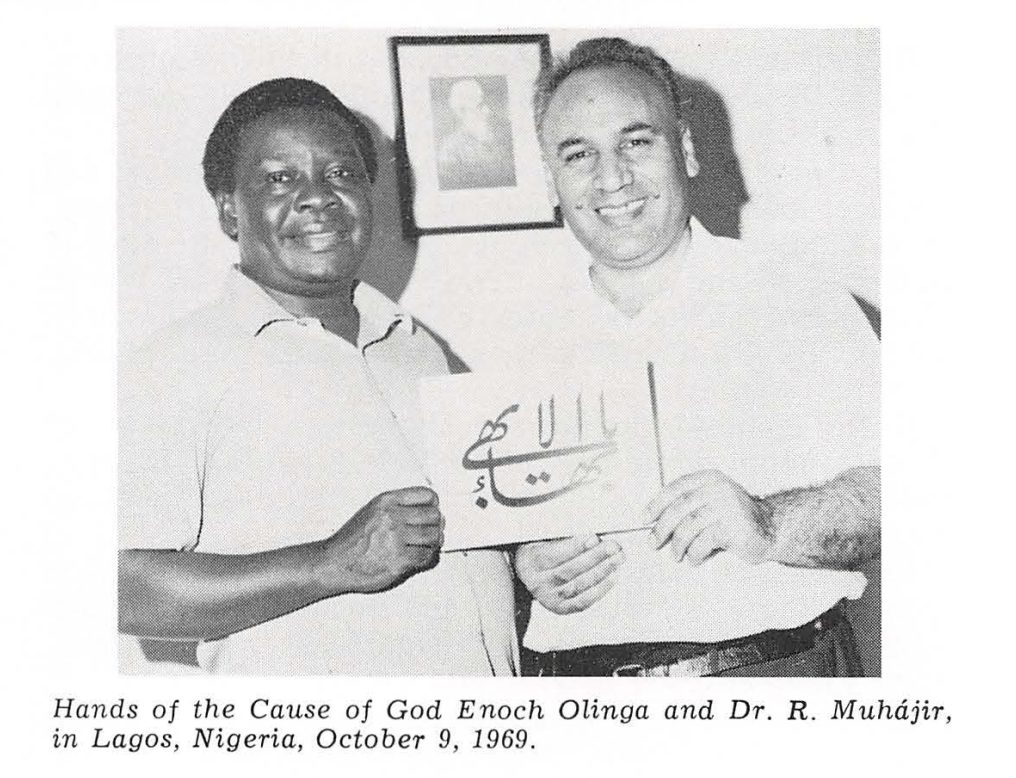

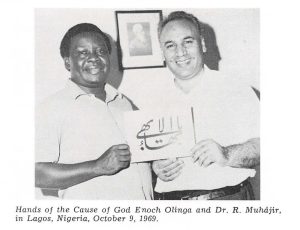

In February 1970, Vajiheh attended a pioneering conference in Tehran addressed by Hand of the Cause Dr. Rahmatu’lláh Muhájir — one of the high-ranking Bahá’ís appointed to safeguard and spread the Faith — and by Mr. ‘Azíz Yazdí, then pioneering in Kenya. Dr. Muhájir’s stirring call for volunteers to fulfil Iran’s goals under the Nine Year Plan (a global plan for teaching the Bahá’í Faith) left no heart unmoved. Afterwards, Mr. Yazdí spoke with Vajiheh, and strongly recommended Cameroon as the place where Iran’s assigned goals were most in need of fulfilment.

At twenty-six, she was venturing into the unknown. With limited English, no travel experience outside Iran, and scant knowledge of Cameroon—a place Iranians generally feared, imagining people slept in trees and risked being eaten—she nevertheless trusted wholeheartedly in the power of divine confirmations. She accepted the challenge. After a brief pilgrimage at the Baháʼí World Centre, she boarded a plane, ready to dedicate her entire life to serving humanity far from home. The young woman who had once been told such solitary travel was unthinkable was now ready to devote her entire life to the service of humanity far far away from home.

Arrival and Early Pioneering in Cameroon (1970–1973)

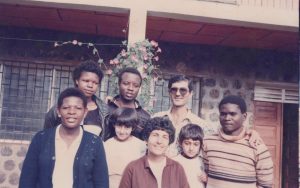

In February 1970, 26-year-old Vajiheh Ighani left Iran for her pioneering post. The only contact she had at her destination was the postal address of an American pioneer called Louise Stewart, who was a school teacher in Yaoundé. Fresh off the plane, she asked the taxi driver to take her to the American Embassy, hoping someone there might know an American schoolteacher. By a stroke of good fortune, an American man at the embassy recognised the name, said Louise taught his daughter, and personally led the taxi all the way to the school. That is how Vajiheh met her very first Bahá’í in Cameroon.

Louise Stewart welcomed her and invited her to stay in her home for a few days. Because Vajiheh already spoke a little English, Louise advised her to serve in the English-speaking part of the country and helped her travel to Douala. From Douala, pioneer Karen Bare then guided her on to Victoria (today Limbe).

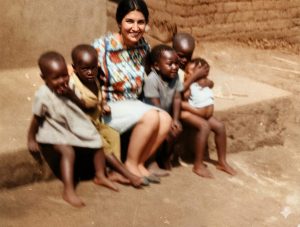

There, Vajiheh was warmly received and taken in by Mrs. Zora Banks, an elderly African-American pioneer who had been serving in Cameroon for many years. Two weeks after Vajiheh’s arrival, another young Iranian woman, Shahin Pezeshkzad, arrived. The two lived with Mrs. Banks in Victoria for a few weeks while they settled in. Everything was completely new: the climate, the food, the language. The first time Vajiheh tasted an avocado (locally called a “pear”) she was startled and did not like it at all, having expected something sweet.

With bouts of malaria a frequent occurrence, and mail from home taking months or even years to arrive, life was challenging. Fortunately, Mrs. Banks, a member of the National Spiritual Assembly (the elected governing council of the Bahá’ís in Cameroon), used her connections at the immigration office in Buea (a nearby town) to assist Vajiheh and Shahin. As a result, both quickly and easily received their residency permits within a few months.

After eight or nine months of being in Cameroon, she felt somewhat confident in her English. In addition to focused practice, she improved thanks to her involvement in Baha’i firesides (informal discussion gatherings held in a home to teach the Faith). As a result, Vajiheh was able to obtain a Science teaching position at a private secondary school near Kumba.

The salary was modest, but being a school teacher gave her a practical source of income and enough time for teaching trips, firesides, and local Bahá’í activities. Living first in Kumba and then in Muyuka, she taught science during the day at a small mission school in Mpundu village, four miles away. Every morning and afternoon she walked the dusty road between Muyuka and Mpundu. In the afternoons and on weekends she held firesides, visited villages, and helped form Local Spiritual Assemblies, serving on local committees as soon as her English allowed. At Ridván 1971, she was elected to the Local Spiritual Assembly of Kumba, her first such service in Africa.

From 1970 until his passing in 1979, the gentle and artistic Hand of the Cause Mr A. Q. Faizí, kept her spirit alive with handwritten letters and postcards. He knew how isolating pioneering can be, and he supported many pioneers with his loving correspondence. Over five years Vajiheh received about fifteen of these messages of support — exquisite calligraphy in Persian, verses from the Writings brushed over delicate water-colour flowers or landscapes. The first, shared with Shahin, was dated 21 July 1970; the last arrived on 12 May 1975. She kept every one, re-reading them whenever isolation pressed in, and decades later would still take them out to show visitors and shared copies with friends.

In 1971 the small band of Baha’is spread throughout Cameroon were charged by the visit of Amatu’l-Bahá Rúḥíyyih Khánum and Violette Nakhjavani on their Great African Safari. The two travelled by Land Rover across the continent, and Cameroon was one of the highlights. They arrived in the South West Province in October 1971 and spent several days in Kumba and surrounding areas. Vajiheh joined them for part of the journey, hosting them in Muyuka and sharing stories of the local believers.

On 21 October 1971, Vajiheh accompanied Rúḥíyyih Khánum and Counsellor Dr Mehdi Samandarí as they addressed more than a hundred students and teachers at Fess Technical College on the subject “The Spiritual Destiny of Africa.” During the same visit, in Kumba, fellow pioneers Shahin Pezeshkzad and Thomas Rowan were married — an occasion of great joy, with Ruhiyyih Khánum present.

Vajiheh was not entirely happy at the mission school in Mpundu and had been trying to obtain a post in Bamenda. When she shared this with Rúḥíyyih Khánum, the Hand of the Cause immediately offered to deputise her for a full year so that she could move as soon as her contract ended. In June 1972 Vajiheh left for Bamenda, free to serve wherever the need was greatest.

Hand of the Cause Dr Rahmatu’lláh Muhájir visited Cameroon several times during these early years (several times throughout the 70s). His visits were filled with words of encouragement: “Teaching is an individual duty like praying or eating”; “Every night we must have a fireside”; “If we hold ourselves accountable when people do not accept, then we will be encouraged to persevere.”

Dr Muhájir’s simplicity left a deep mark on her. During one of his visits in Douala, while waiting for a flight, Vajiheh and a friend visited him at his hotel. They noticed he was living on nothing but bread and cheese bought from a local shop—a lesson in detachment and focus that Vajiheh never forgot.

Other distinguished visitors strengthened the small community: Hand of the Cause Enoch Olinga and his wife Elizabeth, who radiated courage and love; Vajiheh met them in 1970. Hand of the Cause ‘Alí-Muḥammad Varqá (1972), during a visit to Obala near Yaoundé.

At Ridván 1972 Vajiheh was elected to the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of Cameroon — barely two years after her arrival, and still struggling with English. She served for one year. In April–May 1973 she travelled to Haifa as a member to attend the International Convention (the gathering to elect the Universal House of Justice, the supreme governing body of the Faith). One afternoon, while walking in the gardens of the Shrine of the Báb with Karen Bare (American pioneer) and Elizabeth Olinga (wife of Hand of the Cause Enoch Olinga), someone quietly took a photograph of the three women with their arms around one another. None of them realised it at the time, but that spontaneous embrace — dark skin, light skin, and tan — became a widely published image depicting unity in diversity in Bahá’í literature.

Following the International Convention, her friend Bijan Yazdani convinced Vajiheh to travel back to Iran to visit her mother. She travelled with Bijan, his fellow pioneer Nosrat, and American pioneer Karen Bare. Vajiheh was concerned that the shock of seeing her suddenly might cause her mother a heart attack. When they arrived in Tehran, Vajiheh waited nervously in an alleyway around the corner while Bijan, Nosrat, and Karen knocked on the door. When Maliheh opened it, they introduced themselves as friends from Africa. Immediately, the mother asked, “Do you know my daughter Vajiheh?”. When they admitted she was nearby, Maliheh sensed the surprise. Vajiheh stepped out from the alley, and mother and daughter collapsed into each other’s arms in tears of joy.

By the close of the Nine Year Plan in 1973, the girl from Babol who had arrived alone three years earlier now felt at home in Cameroon. She had come to know countless hearts, had carried Bahá’u’lláh’s message to village after village, and Cameroon — with its red dust and radiant, welcoming people — had quietly, irrevocably become her true home.

Continued Travel Teaching, and Appointment as Auxiliary Board Member (1973–1978)

After the triumphant close of the Nine Year Plan in 1973, Vajiheh did not slow down; she simply shifted into a higher gear. She moved between Mamfe, Bamenda, and Buea, living wherever the teaching work required. She travelled the South West and North West Provinces on crowded bush taxis and on foot, holding firesides and deepenings, visiting new believers in their villages, encouraging struggling communities, and helping form Local Spiritual Assemblies. She attended national teaching conferences in Douala, Yaoundé, Bamenda, Mamfe, and Kumba, and regional conferences in Ghana and Nigeria.

In May 1974 she travelled once more with Dr Muhájir, this time to the village of Tinto to admire the beautiful new teaching institute there. Wherever she went, she carried the same radiant smile and the same heartfelt, fearless love. People responded to her because they felt, instantly, that she loved them purely and completely.

Her focus on service was so strong that physical hardships barely registered. A fellow pioneer, Rouhieh Shahidi, recalled visiting Vajiheh in Mamfe around 1975. Her house was very small and humble. Colorful lizards would dart in and out of the front door, running across the floor. While many would have been startled, Vajiheh didn’t even seem to notice them, let alone be bothered; her eyes were fixed on higher things.

Once, waking in the night, she found a tall man moving silently through her house searching for valuables. Instead of fear she felt only peace. She offered a silent prayer and stood motionless. The intruder walked right past her in the dark, never seeing her, and left empty-handed. She returned to bed certain that the same power that had carried her across continents still guarded her doorstep.

In 1977, while living in a small house in Buea overlooking the Atlantic, she received a letter that would change the course of her service for the next several years: the Continental Board of Counsellors had appointed her an Auxiliary Board Member. From that day forward her mandate was no longer only to teach but to protect and encourage every soul and every institution in one of the most vibrant regions of the country.

She threw herself into the new responsibility with boundless energy. She visited chiefs and village elders, sat on mud floors sharing fufu corn and plantains, prayed and slept in believers’ modest homes, and walked for hours under the equatorial sun to reach isolated friends.

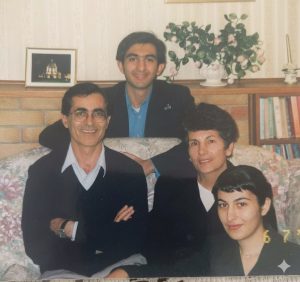

At one of the conferences she attended in 1977 she briefly met a handsome pioneer who had recently arrived from another African country with his sister. His name was Kiumars Vaezi. She thought little of it at the time. After much prayer and reflection, Vajiheh accepted Kiumars’ proposal, believing he would be a true companion in a life of service. A brief courtship followed. On 31 August 1977 they were married in a simple but radiant celebration at her home in Buea. Pioneers, Cameroonian believers, and Assembly members filled the house with song and laughter.

The newly-weds threw themselves back into teaching, often in different towns. Vajiheh moved to Bafoussam to join Kiumars. A few weeks after the wedding Vajiheh was in Bafoussam hosting an elderly visiting couple. While crossing the street ahead of her guests — looking right but forgetting to look left — she stepped into the path of a pick-up truck. The impact struck the side of her head and flung her several metres. She was rushed to hospital with multiple skull fractures and severe brain trauma.

The doctors were grim, but prayers were answered and miraculously she lived. Recovery, however, took more than a year. Memory and emotional stability returned only slowly; hormonal swings from the injury made her moods unpredictable. In what should have been their honeymoon period, Kiumars took care of her day and night with infinite patience and tenderness. The test, instead of breaking them, only deepened their love and their reliance on the power of prayer. By the end of 1978, she resumed service as wife, mother, and as an Auxiliary Board Member.

The accident left a permanent mark; she never quite regained her former mental sharpness or sustained focus. Yet her faith, her love for every soul, and her zeal to serve were utterly untouched — if anything, deepened — by the gift of a second chance at life.

Marriage, Family, and Continuing Service (1978–1994)

The next sixteen years were filled with further service. After her recovery the couple moved where needed, following the by then standard routine of living somewhere until a Local Spiritual Assembly could be established, then moving on elsewhere so they can open new localities. They lived in: Bafoussam (French-speaking West), Baba 1 village and Bamenda (North West), Kumbo (further inland, a goal of the Seven Year Plan), Ngoundéré (the largely Muslim Far North, where no Bahá’ís existed when they arrived) and finally Buea again.

Martha was born in Bafoussam in 1978, and Lessan in Bamenda in 1981. Even with young children, Vajiheh’s service never wavered.

Wherever they went, the pattern was the same: Kiumars and Vajiheh would rent a simple house, open their doors day and night, and turn it into a centre of teaching and love. The partnership between Kiumars and Vajiheh was truly complementary, especially during their years in Kumbo. Kiumars was the technical expert; he acquired a Gestetner duplicating machine (a cyclostyle) and set it up in their home. He worked tirelessly to produce study guides and deepening materials for the Provincial Teaching Committee, churning out documents that were vital for the community’s growth.

While Kiumars managed the publications and the study classes, Vajiheh was the connector. She was the one who went out to the markets, on dusty roads and thatched huts, inviting people in. Their humble living room was always full. In Kumbo they ran weekly deepening courses that produced a generation of steadfast young believers (Kiven Sheidu, Christopher Ngum, Massanjeh Elijah, Martin Fusung, Isaac Leh, John Tenning, Martin Nzokeh, Abongwa Gabriel … names Vajiheh could still recite decades later with shining eyes).

Despite their limited means, Vajiheh maintained a profound sense of dignity for the Faith. A former student recalled going to the market with her to buy second-hand clothes. She would carefully sort through the piles, select a specific item, and hold it up, saying, “This is for visiting authorities.” She compartmentalized her simple wardrobe not for vanity, but to ensure that when she met with officials to represent the Cause, she did so with the utmost respect and propriety.

Maliheh Sabetian (Khánum Buzurg), Vajiheh’s mother, had joined the family in 1979 after the Iranian Revolution made return impossible. With her limited English and colourful personality she became a legendary figure: standing by the roadside, smiling at everyone who passed, holding out a pamphlet and saying in her simple English, “This Bahá’u’lláh — Jesus Christ come again.” Years later a new believer would tell the family, “I enrolled because of that sweet old lady who used to smile at me on the road.”

As Auxiliary Board Member, Vajiheh travelled constantly. She visited every corner of the South West Province and beyond: chiefs’ palaces, remote villages, muddy roads. She encouraged women to study the Writings, youth to pioneer, children to memorise prayers. She never refused an invitation, never complained about the heat or the mud or the malaria that came again and again.

In 1989 with guidance from Institutions, they moved to Ngoundéré in the north of Cameroon. For two years they were the only Bahá’í pioneers in that huge, overwhelmingly Muslim region. They served patiently and lovingly, but for the children’s future they eventually returned south.

They moved back to Buea, where Vajiheh had lived many years ago and where Dr. Samandari still resided.

By the early 1990s Martha and Lessan were teenagers. Neither child had citizenship of any country: Cameroon would not grant it to children of non-citizens, and post-revolution Iran refused it to Kiumars and Vajiheh because they had had a Bahá’í marriage in Cameroon, and Iran didn’t recognize the Bahá’í faith. Passports, university admission, and even simple travel became impossible. After long and earnest consultation with institutions and family, Kiumars and Vajiheh made one of the hardest decisions of their lives: for the sake of their children’s future they would leave the land Vajiheh loved so dearly.

Migration to Australia via India and New Life in Adelaide (1994–2010)

In June 1994 Kiumars, Martha (15), and Lessan (12) left first and discreetly as Khánum Buzurg’s mental health had become fragile; any hint of permanent departure could have provoked a dramatic reaction that might have prevented them from leaving. They slipped away without even saying goodbye to most friends.

Vajiheh stayed behind to pack twenty-four years of memories into a few suitcases, settle affairs in Buea, and prepare her mother. Kiumars and the children spent a few weeks in Delhi, then moved to Panchgani in Maharashtra, where Kiumars taught and the children studied at the New Era Bahá’í School. They waited there for several months until confirmation finally came that their application to Australia had succeeded. Only then did they send word for Vajiheh and Khánum Buzurg to join them.

Vajiheh was overjoyed to be reunited with her family. The principal, Dr. Vasudevan Nair, welcomed them like family; his own brother Bhaskaran Nair had pioneered to Cameroon years prior. (Decades later, that same brother’s son, Vahid Bhaskaran, would marry Martha.)

On 5 May 1995 the five of them landed in Adelaide. Kiumars’s brothers, long settled in Australia, met them at the airport with open arms and helped them find a house in the southern suburbs.

The culture shock was brutal. Cold winters, silent streets, neighbours who looked away instead of responding to greetings. Vajiheh tried at first to do exactly what she had always done: walk the streets smiling at strangers, offering pamphlets about Bahá’u’lláh. The reception was icy. But she refused to retreat into isolation.

Within weeks Kiumars was elected to the Local Spiritual Assembly of Brighton (later Holdfast Bay). Together with his brothers and the Assembly they rented a shopfront on Brighton Road that became the Brighton Bahá’í Information Centre. Vajiheh threw herself into serving here with the same energy she had once given to village teaching institutes. She helped set up a beautiful library, arranged flowers, made cups of tea, and sat smiling at the desk ready to talk to anyone who walked in.

When the community later bought a building outright to be the new centre and moved there, it became a true hub: firesides, holy day celebrations, children’s classes; Vajiheh was there almost every day, greeting friends and seekers alike. She resumed her beloved home visits, driving to Onkaparinga and the southern suburbs with Tahereh Pourshafie, encouraging study circles and children’s classes.

Martha studied occupational therapy and married Vahid Bhaskaran. Lessan studied software engineering and moved to Ballarat. Rather than let him struggle alone, Vajiheh moved with him for a whole year, keeping him company in their little flat. Even there she made her passion for teaching known; the Ballarat friends still remember her warmth and encouragement. She later returned to Adelaide and resumed her daily service at the Bahá’í office and visiting the friends.

Vajiheh never stopped missing Cameroon. She kept photographs of Cameroonian friends all over her desk and frequently re-read the handwritten letters from Mr Faizí. Her copies of Dr Muhájir’s biography and The Great African Safari (documenting Rúḥíyyih Khánum’s journey) are heavily underlined and worn from use. Two copper plaques bearing the Greatest Name (a Bahá’í symbol), hand-hammered and engraved by villagers in Democratic Republic of Congo in 1973 (while on a visit to her dear friend Behin), accompanied the family to Australia and hung in the family home.

The fire that had carried her from Babol to Bamenda to Adelaide still burned brightly. It simply expressed itself now in quieter ways open to her in a more individualistic and materialistic society: visiting and deepening existing believers, helping run the centre, and showing her love to whoever crossed her path.

Later Years, Passing, and Legacy

Around 2010 the first signs of memory difficulty appeared. Vajiheh would forget details of recent occurrences. At first the family thought it was simply age and the lingering effects of the 1977 accident. But the decline was steady and irreversible. By 2015 a diagnosis of dementia was confirmed.

Even then she refused to stop serving. She kept walking — kilometres every day with her walker, trying to get to her beloved Bahá’í office. She visited the local Foodland supermarket regularly, sometimes three or four times a day as she forgot she had been there already. She loved the bustle, and the chance to smile and talk to people. Neighbours and shopkeepers learned to recognise the quirky Persian lady with the radiant smile.

In her final years, she still insisted on attending Feasts and Holy Days. When friends would ask “How are you Vajiheh?”, she would respond: “By seeing you I am now very happy.”

In late 2025 her mobility began to fail. She spent her last two months bed-bound in hospital and a temporary nursing home, still trying to smile at every passer by. Whenever someone would visit her she would beam, think carefully and say: “Khodaya, che gooneh to ra shokr namayam?” (O God, how can I ever thank Thee?)

On the morning of 22 November 2025, with Martha at her bedside and Kiumars gently resting his hand on her forehead reciting a prayer, Vajiheh quietly drew her final breath. She was 81 years old.

News spread instantly among the Cameroonian Bahá’í community scattered across the world. Within hours messages poured in from people who had not seen her in thirty or forty years yet still remembered how she had affected them. Some even had detailed memories to share. The National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of Cameroon sent a heartfelt official tribute.

The funeral was held on a sunny Adelaide spring day at the Heysen Chapel, Centennial Park Cemetery. Family and friends filled the room. Prayers were recited in English and Persian. Martha and Lessan gave a heartfelt eulogy of their special mother who affected so many hearts.

In a final gift of providence, Mrs Helen Otia — the Cameroonian believer who had succeeded Vajiheh as Auxiliary Board Member in 1994 — who was visiting her relatives in Melbourne was able to attend the funeral with her nephew Elvis. As the casket was lowered, Helen read the very same prayer for the departed that Kiumars had recited at the moment of passing.

Vajiheh leaves behind a husband who walked every step with her for forty-eight years, two children and their spouses, six grandchildren, and many hundreds — perhaps thousands — of spiritual children across Cameroon and beyond whose lives she touched with a love so pure it is still spoken of with tears half a century later.

This legacy was beautifully captured by fellow pioneer Mr. Niaz Bushrui, who wrote:

She sowed the seeds of love in distant lands,

With gentle heart and tireless hands.

Her voice was a beacon, her smile a light,

She turned each shadow into radiant sight.

Beside her stood a soul so true,

A partner strong, her vision too.

Together they built a legacy bright,

A home of service, a flame of light.

Now heaven holds her, yet here she stays,

In every soul she taught to praise.

Her mission lives, her flame burns true,

Through her children’s steps, her spirit renews.